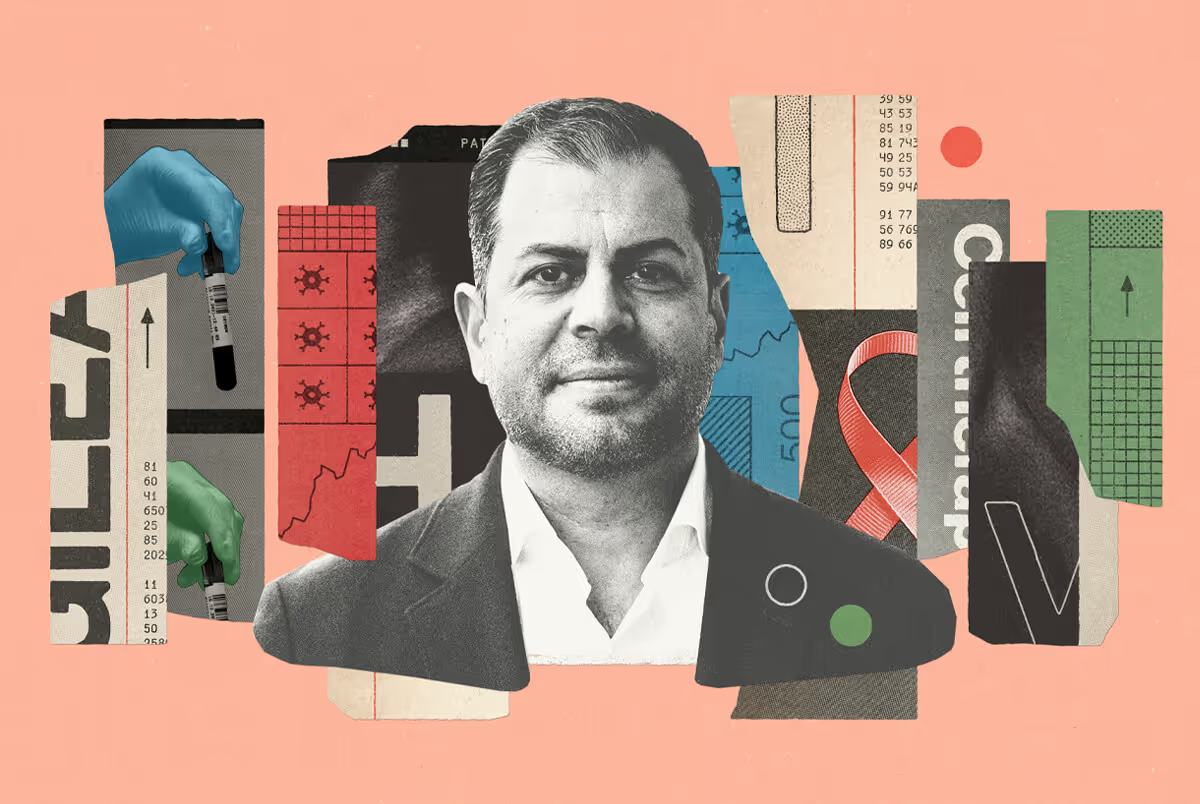

Planning one’s future is often top of mind for young adults as they work to establish themselves in the world. It’s not always simple, though. For 31-year-old Brendan Ardagh and 25-year-old Lila Willdey, the process must be balanced with the uncertainty of living with a rare and incurable genetic condition.

Brendan is a tech entrepreneur from Cape Town, South Africa, now living in Toronto. Lila is a teacher from the small town of Fort Augustus, PEI. On the surface, Lila and Brendan may not seem to have much in common, but they’re both young, ambitious dreamers focused on building lives and careers that will set them up for rich and fulfilling futures.

.avif)

Like all young Canadians, they face uncertainty — but they also grapple with something more concrete: Fabry disease, a rare and complex condition with an unpredictable prognosis. That’s because having a rare disease like Fabry comes with unique challenges, such as a prolonged path to diagnosis, finding effective treatment, and explaining the complicated condition to friends, family, and possibly even future partners.

Fabry disease is a genetic condition that affects roughly 500 people in Canada. It’s caused by a spontaneous or inherited mutation of the galactosidase alpha (GLA) gene, and can be passed through generations of a family via the X chromosome.

DID YOU KNOW?

Slowing progression is a top priority

“Patients with Fabry disease are deficient in an enzyme that breaks down a complex molecule (called globotriaosylceramide) within the cells,” explains Dr. Shaymaa Shurrab, a geneticist and metabolic disorder specialist at McMaster University. “As a result, these molecules accumulate over time, causing inflammation and damage to multiple organs, including the heart and kidneys. Without intervention, most patients would die from complications within their fourth or fifth decade.”

For Lila and Brendan, thankfully, the picture isn’t as dire as it might appear at first glance. There are multiple approved Fabry treatments and ongoing clinical trials, though access remains limited by factors such as age and location. While none are curative, the available treatments can help reduce painful symptoms and slow disease progression.

“Early diagnosis and treatment are critical,” says Dr. Shurrab. “Nowadays, we’re seeing increased life expectancy thanks to the introduction of Fabry-specific treatments. That’s why it’s important to identify Fabry patients as early as possible to assess their eligibility to start treatment and to monitor their symptoms’ progression. They’ll then require lifelong follow-ups by a multidisciplinary team.”

Building a good life amidst symptoms, medications, and appointments

People are born with Fabry disease, but they may go years or decades before their diagnosis is confirmed. Lila, for instance, was 21 when she first learned she had inherited the condition.

“Once I was diagnosed, I was looking back and it was just like, oh, yeah, it all makes sense now,” she recalls. “I had symptoms as a child but didn’t realize they were related to Fabry. I remember playing sports as a kid and experiencing so much pain in my feet. I’ve also always had brutal stomach pain, but I just learned to live with it.”

It wasn’t until Lila was tested in 2022, after her mother, aunt, and cousin had all tested positive for Fabry, that she learned the pain she’d been living with her whole life was an early manifestation of a disease that could eventually threaten the functioning of her heart, kidneys, and even brain, as well as impact family planning for Lila and her partner, Mackenzie.

Lila started treatment as soon as possible, but living with a rare disease comes with costs and compromises. She faces frequent medical tests and appointments, often requiring travelling to Halifax (approximately 400 km) to see the nearest Fabry specialist — a significant time and financial burden for a young adult building her career.

“Fabry will obviously always be a part of my life, but I don’t want it to define my life.”

As Lila juggles these distant medical appointments and the hectic demands of a budding teaching career, she’s also trying to find the right mix of lifestyle adjustments and medication that will alleviate her symptoms and keep her body strong and healthy for as long as possible.

“I’m in the process of trying to find a medication that works for me,” Lila says. “I had one that was helping my pain, but the side effects were unbearable. I’m testing out a new one now. If I could just find something that works for me — that allows me to go for walks, go skating, spend time with my friends, travel, have children, continue teaching, and just create a healthy life — it would mean everything. Fabry will obviously always be a part of my life, but I don’t want it to define my life.”

Finding community in a new country

When Brendan was 13 years old, his family got the news that one of his uncles had fallen ill. Then another, and another. Eventually, five uncles in total were diagnosed with Fabry disease. Brendan’s parents arranged to have him and his sister tested. Both tests came back positive.

“From there, I was just told that I’d need further checkups,” recalls Brendan. “My parents did the research, but I was shielded from it. I had no symptoms and seemed to be okay.”

As he grew older, however, Brendan came to realize that no matter how healthy he felt, Fabry disease would forever be a part of his life, a genetic legacy set to shape his future one way or another. This understanding expanded profoundly after moving to Canada and meeting Fabry patients from outside his own family for the first time.

“This disease doesn’t feel as unmanageable when you meet with other people facing the same challenges.”

“I learned most of what I know about Fabry after coming to Canada four years ago,” Brendan says. “I connected with the Canadian Fabry Association and attended a conference in Calgary. It was important for me to find community. This disease doesn’t feel as unmanageable when you meet with other people facing the same challenges.”

“Like a race against time”

Today, Brendan remains mostly symptom-free, aside from some numbness and circulation issues that fall below the treatment threshold. Further testing has shown that his type of Fabry is characterized by late onset, similar to how it presented in his uncles. But how late that onset will be is still uncertain.

“I need to be careful,” says Brendan. “I see my GP every few months and a specialist once a year to monitor my heart. I exercise frequently and eat pretty well. With Fabry in my life, I don’t want to let myself be unhealthy in any other way, especially as a result of my own habits.”

As an ambitious entrepreneur, Brendan is working hard to build his career, having founded an AI startup focused on the construction industry. He’s concerned about how Fabry could impact his productivity in later years, and is accomplishing as much as he can now. “I’m working hard to be financially stable before my symptoms progress and I need treatment,” he says. “In a way, my life feels like a race against time.”

More options, better outcomes

For both Brendan and Lila, life today is about managing their health as well as they can and setting themselves up for success. Brendan hopes his rigorous exercise and diet regimen will provide added resilience when more serious symptoms arrive. Lila is also keeping as active and healthy as possible, staying in tune with her body, and continuing to explore different medications in the hopes of finding something that works well for her.

They’ve both also gotten involved with Fabry advocacy initiatives and are deeply invested in the state of research, funding, and access to new treatments. The course of both Brendan’s and Lila’s lives will be in no small part affected by the diversity of treatment options available to them as their conditions progress.

“The reality is at some point my health is going to become a big issue,” says Brendan. “And when that happens, I’m hopeful there will be treatment options available to support me through it.”

.avif)

Hope, according to Dr. Shurrab, is one of the most important parts of this journey. “There are many possible therapies that are coming down the pipeline,” she says. “It’s crucial that these patients feel hopeful about the future — that one of these options will work for them. As a clinician, I make sure to keep my patients updated on promising trials and treatment options.”

None of us know what the future holds. But for Canadians diagnosed with rare genetic conditions like Fabry disease, that uncertainty underscores the importance of taking care of yourself now and making sure that you’re set up for the future. Brendan and Lila can still chart bright, meaningful futures — but only if our health care system is prepared to support them along the way.

If you’ve been diagnosed with Fabry disease, either recently or in the past, there's a community of patients, caregivers, and clinicians here to support you. To learn more about Fabry, seek support, or access additional resources, please connect with the Canadian Fabry Association.

Created by Patient Voice with support from Chiesi Global Rare Diseases.

.avif)