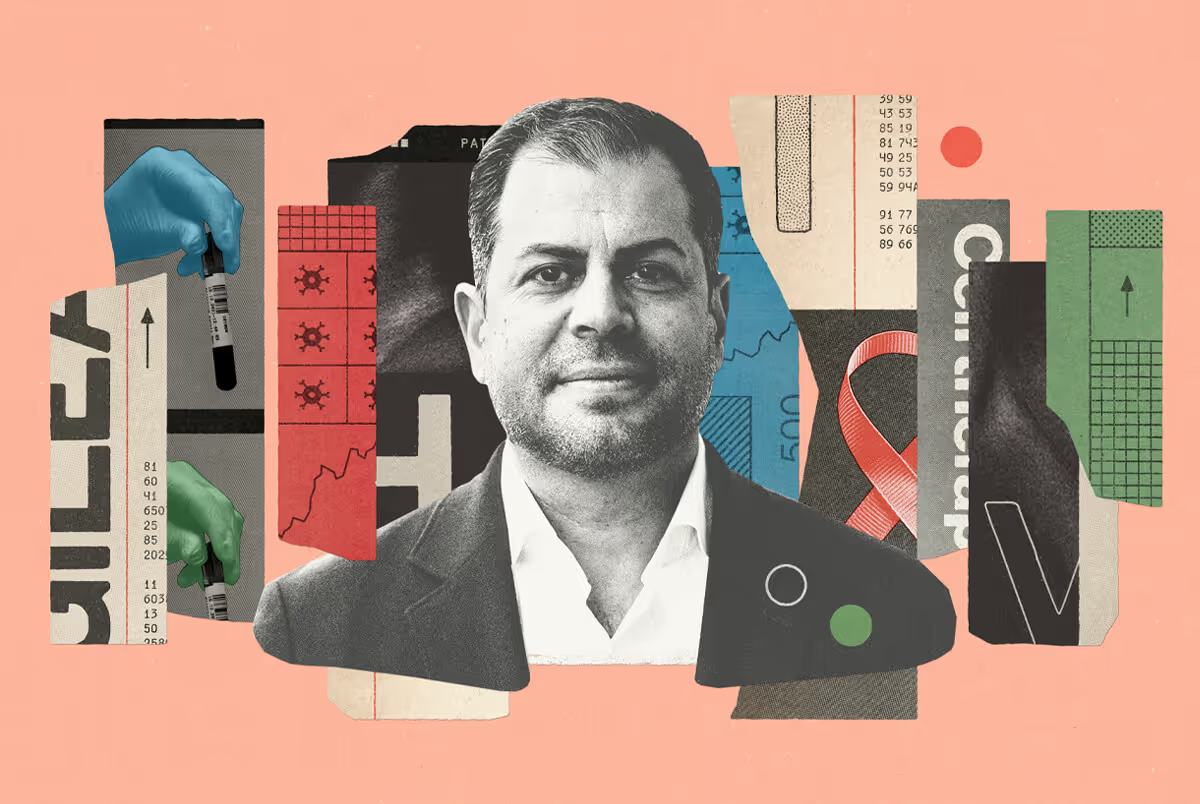

“Bert and I had only been together for about a month when we decided to go on a canoe trip in Algonquin Park. A kind of relationship trial by fire. We were both looking for something stable and serious, someone to love for the rest of our lives. We figured if we could survive five days together in the wilderness, we could survive anything

It was one of the best weeks of our lives. The very next year, we got married at City Hall. And then it was happily ever after – until my cancer scare in 2015 reminded us that ‘happily ever after’ wasn’t necessarily promised. After that, we were very aware that no one knows how much time they have. We decided to take some time off and just enjoy each other. We saved up and, four years later, we both took a one-year sabbatical from our teaching jobs for a little jaunt, an around-the-world trip visiting Japan, New Zealand, Australia, and Bert’s family in Europe.

Our trip had just begun when I noticed that Bert was walking slower than usual. I usually had to jog to catch up with his 6’4” strides, but in Tokyo it was him falling behind. By the time we reached New Zealand, it was clear that something was very wrong. A Christchurch-based neurologist was the first to say that it looked like ALS.

.avif)

Suddenly our time was very limited. From the beginning, Bert was adamant about documenting everything. He had always been a champion of representation, and he saw an opportunity to share his story and put a face to his disease, especially for LGBTQ people. He started posting about our lives and his illness. As soon as Bert put himself out there, people started reaching out and saying that his story was helping them.

Bert was always helping everyone. Once he was gone, one of the hardest things was knowing he wouldn’t be there to help me through my grief. Except that he still found a way.

When we were in Australia, Bert had gone shopping in secret. He spent the rest of the trip writing away without letting me see what he was working on. And now here I am, building up the courage to open the first of 30 birthday cards. I’ll be in my 70s and he’ll still be checking in on me on my birthday, making sure I’m okay.

When Bert received his official ALS diagnosis, we both started bawling. Bert was so apologetic, telling me over and over again that he was sorry, though neither of us thought for a second that it was his fault.

I know that part of what he was trying to apologize for was what was going to come next. The plan had always been that Bert was going to retire first, that he would then have time to help me with everything – at home, in my classroom. That was not how it was going to be. I went into caregiving mode right away. It’s hard to explain that mindset shift and how strange it is to have those old visions of the future with this person coexist with the new reality of helping them get dressed, carrying them up and down the stairs, and helping them communicate when they lose their ability to speak.

Bert’s family isn’t in Canada, and my family is MIA, so all of it was on me. On the one hand, it came naturally, because we always did everything together anyway, and because I wanted to do everything for him and to have every moment I could with him. If Bert wanted to stay up late and watch TV, or if he wanted to go to the park, I would stay up late or go to the park, not because he needed my help, but because I wanted that one more memory with him. But, no matter how much you love someone, caregiving is taxing.

I was still teaching, online in the midst of COVID, and I was getting maybe one or two hours of sleep a night. I was exhausted and I was being pulled in every direction. In some ways, I’m sure it was similar to what it feels like to be a new parent. But the outlook is very different with a baby than it is with a terminal disease.

When you’re a caregiver, people always tell you to make sure you also take care of yourself, to take time for yourself, but I just couldn’t. Not knowing how much time we had, I felt that every moment needed to be about him. Because there would be too many moments in the future without him.

And now that I’m living in that future, I look back and I’m just so grateful that I was young enough and healthy enough to have the ability to be there for him in all those ways, as we promised, in sickness and in health.

.avif)

Death doesn’t look like it does in Hollywood movies. There was no sitting around, holding hands, and tearfully saying our goodbyes. On the night it happened, Bert had been awake for 36 hours. I had been up for God knows how long. We were both so tired. There was no chance to prepare and think, ‘Oh, this is the moment.’

When Bert finally fell asleep, I carried him up to the bed. I cleared his airway for him. He put his hands on his chest in the shape of a heart. And then he was not there anymore.

I dressed him in his wedding suit, because that was what he’d wanted. And then they came to take him away. The stillness when everyone left was surreal. There had long been a breathing machine running in our home.The sudden silence was so loud.

Dealing with grief is impossible. It doesn’t come all at once. And, when you start to feel better, it’s certain that you’ll soon feel worse again. I can be doing okay one minute, and then suddenly my knees buckle. I go back and forth all the time. I can only try to make it one day, sometimes one hour, at a time. There’s no solution to grief. It’s something you have to experience and live. You have to find ways to live in it.

Earlier in his ALS journey, Bert had suggested that we get a dog. So one afternoon we went down to the Humane Society and came back with Havermout. Bert knew that having this living creature loving me and depending on me would give me the motivation to keep going. He was right. Havermout and I walk down to the cemetery every day. Sometimes we visit Bert’s old school and see the rainbow bench they installed and dedicated to him. It’s soothing to be reminded of the good Bert left in the world.

Grief isn’t linear. It’s oscillating. It comes when you’re not ready for it, and it stays as long as it wants. Some people say that grief s just love that can’t find its home. I’m not letting go of my love for Bert, so I must learn to carry the grief, on the days when it’s light and on the days when it’s heavy."